InsightS

Trademark disclaimers and their effects on similarity assessments

In Thailand, trademark law allows the trademark registrar to order a trademark applicant to give up exclusive rights to certain parts of their trademark. This occurs when a mark, while registrable in its entirety, contains marginal components which are non-distinctive or common to the trade for the designated classes of goods or services. This legal mechanism protects trademark owners’ rights while preserving the public’s freedom to use disclaimed terms or images. Consequently, other businesses may incorporate these disclaimed elements into their own marks, provided their overall trademark does not create confusion with the registered ones.

Beyond registrar-mandated disclaimers, an applicant may voluntarily disclaim a component of their trademark upon filing an application. This proactive approach typically arises when applicants recognize common or non-distinctive elements within their marks and seek to expedite registration by anticipating potential disclaimer orders from the registrar.

Given the prevalence of disclaimers in Thai trademark practice, a critical legal question emerges: should disclaimed elements factor into trademark similarity assessments? This issue has been addressed through decisions from both the Trademark Board and the Supreme Court, offering valuable jurisprudential insight.

Trademark Board’s prevailing view: excluding disclaimed elements

The Trademark Board has shown an inconsistent approach to this question, although most decisions tend to set aside disclaimed elements when assessing degrees of similarity with prior marks.

Decision no. 256/2556 (Ceiling Queen Energy Board v. Queen Original)

In this decision, the Board found the appellant’s mark to be confusingly similar to the registered mark. The Board concluded that the disclaimed components “Ceiling Energy Board” and “Original” were non- essential elements of both marks, leaving “QUEEN” as the only essential element. The marks were therefore deemed so visually and phonetically similar that they could lead to public confusion.

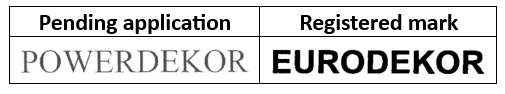

Decision no. 293/2556 (POWERDEKOR v. EURODEKOR)

The Board applied the same methodology in this case, finding the trademarks similar due to their identical essential element “DEKOR.” This conclusion stemmed from disclaimers for “POWER” and “EURO,” which the Board ruled were thus non-essential portions of the marks:

“Although the appellant’s trademark also includes the word ‘POWER,’ the appellant has disclaimed any exclusive right to use the word ‘POWER.’ Therefore, that word is not an essential part of the mark. Similarly, although the registered trademark includes the word ‘EURO,’ the owner of the registered trademark has disclaimed any exclusive right to use the word ‘EURO,’ so that word is also not an essential part of the mark.”

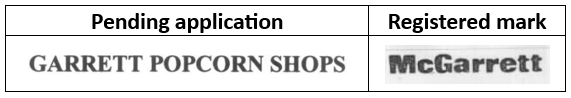

Decision no. 598/2556 (GARRETT POPCORN SHOPS / McGarrett)

In this case, after concluding that “POPCORN SHOPS” was disclaimed and thus non-essential, the Board found that “GARRETT” was confusingly similar to “McGarrett”. This finding directly resulted from treating disclaimed components as non-essential elements.

The outlier Trademark Board decision: breaking from the exclusionary pattern

The Board diverged from its previous stance in Decision 10/2558, regarding the following trademarks:

It found the appellant’s mark confusingly similar to the registered mark, despite the appellant’s disclaimer of the word “SolaShield.” Contrary to previous decisions, the Board reasoned that the disclaimers do not remove the component from the mark for similarity assessment purposes. The Board further noted that due to “SolaShield’s” size and visual prominence, it remained a significant trademark element.

The Supreme Court’s unified approach: a holistic similarity analysis

Unlike the Board’s inconsistent rulings, the Supreme Court has established clear, consistent precedent. The Court takes a comprehensive approach, considering all elements of a trademark, including disclaimed ones, in its similarity assessments.

Decision no. 8725/2554 (California Wow Women v. WOW World of Women)

In Supreme Court Decision No. 8725/2554, the Court found that the appellant’s trademark, with a disclaimer for “CALIFORNIA” and “WOMEN”, was not confusingly similar to the registered trademark, with a disclaimer for “WORLD OF WOMEN”. The Court reasoned that trademark similarity evaluations must consider entire marks, with disclaimed elements retaining their significance rather than being deemed non-essential.

Decision no. 8542/2560 (POWERDEKOR v. EURODEKOR)

This approach was reaffirmed in Supreme Court Decision No. 8542/2560, where the Court reviewed the same marks from Board’s Decision No. 293/2556, but reached opposite conclusions. The Court clarified that disclaimers only prevent trademark owners from claiming exclusive rights to disclaimed parts; they neither diminish the elements’ weight in similarity assessments nor separate them from the overall mark. Therefore, the disclaimed words “POWER” and “EURO” in the latter mark must be considered in the context of similarity assessment for both visual and phonetic aspects. The Court ultimately ruled that the marks were not confusingly similar.

Conclusion

The treatment of disclaimed elements in trademark similarity assessments reveals inconsistency at registrar and Board levels. However, the Supreme Court has established clear precedent: disclaimed elements remain relevant in similarity assessments, with marks’ overall impressions being paramount.

This jurisprudential divide appears to be addressed by the Thai Department of Intellectual Property (DIP)’s 2022 Manual for the Consideration of Trademark Registration. While the DIP initially aligns with the approach treating disclaimed components as non-essential, its guidelines also stipulate that similarity assessments must consider overall impressions, dominant features, and pronunciation, embracing the Supreme Court’s established jurisprudence.

This evolution suggests a movement toward the Supreme Court’s holistic approach, potentially bringing greater consistency to Thai trademark practice.

References:

[1] Trademark Act B.E. 2534 (1991).

[2] Umporn, C. (2019). Issues Regarding Effect of Trademark Disclaimer Under Section 17 of the Trademark Act B.E. 2534. Graduate Law Thammasat University Journal, 12, 585-596.

Trademark Examination Manual of the Department of Intellectual Property, B.E. 2565 (2022).

[3] Bulldog Holdings Limited v. Department of Intellectual Property, Case No. 8725/2554 (2001).

[4] Power Dekor Group v. Department of Intellectual Property, Case No. 8542/2560 (2017).

[5] Trademark Board Decisions No. 256/2556, No. 293/2556, No. 598/2556, No. 10/2558.

[6] Manual for the Consideration of Trademark Registration, B.E. 2565 (2022).